— ClassicsToday.com

Peter Boyer’s Symphony No. 1 was commissioned by the Pasadena Symphony, and premiered by that orchestra under his direction in April 2013. The three-movement, 24-minute symphony is dedicated to the memory of Leonard Bernstein.

The symphony is the centerpiece of a new recording of Boyer’s music by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the composer at historic Abbey Road Studio One in 2013. Released worldwide by Naxos in its American Classics Series in February 2014, the recording also includes four other Boyer orchestral works. It has been broadcast on over 150 radio stations around the U.S. and abroad.

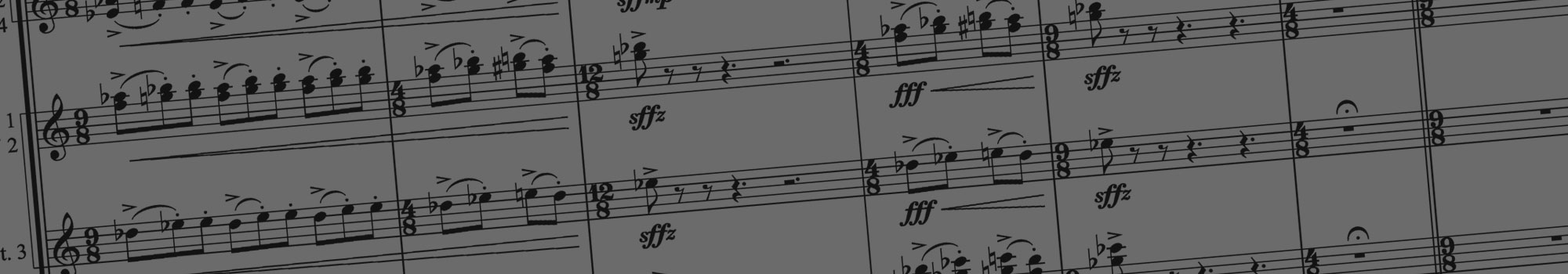

Instrumentation

3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.3(III=cbsn)—4.3.3.1—timp.perc(4,opt5)—harp—pft(=cel)—strings

Movements

I. Prelude: Andante — Doppio movimento, con spirito — Andante, subito più sereno

II. Scherzo/Dance: Presto, molto vivace — Meno mosso [Trio] — Tempo primo

III. Adagio, un poco rubato — Un poco più mosso, con moto — Un poco meno mosso — Più energico, gioioso (l’istesso tempo)

Duration

24:00

Composition Date, Commission, and Dedication

Composed 2012-13

Commissioned by the Pasadena Symphony Association

Dedicated to the memory of Leonard Bernstein

Critical Acclaim

“Boyer, who claims more than 300 performances by more than 100 orchestras, writes in a fluent, powerful style that fuses conservative American currents with Hollywood-ish size and populist sentiment… The three-movement work is dominated by an 11-minute long third movement, an absorbing, eventful Adagio with beautiful, written-out solo riffs…”

— Gramophone

“Classical music listeners apprehensive about ‘new music’ have nothing to fear, and everything to love, about Peter Boyer. The American composer writes music in a neo-romantic style with an unabashedly direct and popular appeal… His Symphony No. 1, a tribute to his muse Leonard Bernstein, is a stirring work, filled with soaring, ‘American sounding’ themes and propulsive rhythms… a recording that’s sure to win him many new fans.”

— WRTI (Philadelphia)

“The final Adagio has an evocative melody that slowly builds up, making full use of the different harmonic effects of the orchestra. This is wide-screen music to play at full volume and become immersed in; it has the strong feeling of being a theme to an epic film…”

— MusicWeb International