Commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts for the 90th anniversary season of the National Symphony Orchestra (2020-21), Balance of Power was funded by former U.S. Ambassador Bonnie McElveen-Hunter, Chair of the Board of Governors of the American Red Cross, in honor of the 95th birthday of her friend and mentor, Dr. Henry Kissinger, former U.S. Secretary of State.

Instrumentation

picc.2.3(III=corA).Ebcl.2.bcl.2.cbsn—6.4.4.1—timp.perc(4-5)—harp—pft(=cel)—strings

Movements

I. A Sense of History

II. A Sense of Humor (Scherzo politico)

III. A Sense of Direction

Duration

18:30

Commission and Dedication

Composed 2019

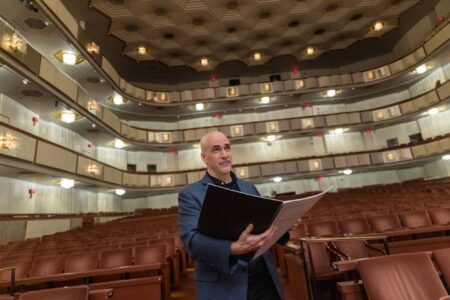

A commission of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts — Commissioned by Ambassador Bonnie McElveen-Hunter for the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, D.C., Gianandrea Noseda, Music Director, in honor of the 95th birthday of Dr. Henry Kissinger